The earliest book covers weren’t covers as we know them. They were tubes in which scrolls were kept. Jesus went to the synagogue at Nazareth and there read from the scroll of the book of Isaiah. The scroll would have been fetched for him by an attendant who removed it from a shelf where it likely was kept in a protective tube.

Centuries later, handwritten books featured not only elaborately illustrated pages but finely wrought covers. The largest books, such as Bibles, often had covers made of wood, from which we get the term “boards” for the front and back covers of a hardback book.

The book trade flourished in the seventeenth century. By that time printing had become far advanced, and books were affordable by people of means. Covers were tooled leather, which persisted into the twentieth century.

At home I have an elegant forty-volume set of the works of John Henry Newman. The books were printed in the late 1870s. The covers are stiff leather, with prominent ribs on the spines. The books look handsome on their shelves, but only the golden lettering on the spines reveal what the books contain.

Dust jackets with flaps began to be used in the 1850s, and by the 1890s most books sported them. Of course, back then nearly all books were hardbacks, paperbacks being a rarity. Early dust jackets made up for simplified bindings, which no longer were visible. It was cheaper to make dust jackets than fancy bindings. This was true even after cloth covers replaced leather covers. Cloth covers—then as now—consisted of stiffened cardboard (still “boards”) over which cloth was glued.

Once cloth began to predominate for covers, it was possible to add artwork inexpensively directly to the cover. Adding artwork to leather covers could be done, but it required time-consuming tooling. Eventually dust jackets took over the artistic task entirely, and we ended up with the sort of cloth covers seen today: usually monochromatic, with black and deep blue being the two most common colors.

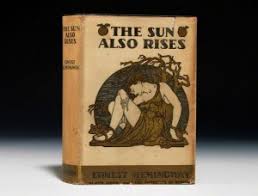

The covers themselves are blank, but the spine include the title, author name, and perhaps the publisher’s logo. Artwork is to be found on the dust jacket, as in the pictured cover of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926).

Soon the artwork was more than just artwork. It became a marketing device for the book. Publishers came to realize that it wasn’t enough to have an artsy cover, as with the Hemingway book. What was needed was an attractive cover that made clear the genre of the book and said enough about the book to induce the prospective buyer to take the book off the book store shelf. Unless the buyer hefted the book and turned its pages, it was unlikely a sale would be made. A cover that intrigued, rather than just looked pretty, often was enough to get past that crucial first step.

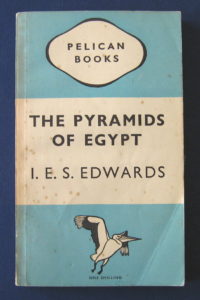

Paperback books were issued as early as the nineteenth century, but they didn’t come into prominence until after World War II. In 1935 Penguin began issuing paperbacks with the now-famous penguin logo. It was a cheap way to distribute books that likely wouldn’t have mass appeal, such as Classical works or works in niches other than fiction. The Pelican paperback on The Pyramids of Egypt (1947) is an example.

After the war, other publishers followed suit, and mass-market paperbacks became ubiquitous in the 1950s. For the first time, at least in a concerted way, book covers began to have a distinctly marketing function. They no longer were merely protective or merely artistic. The still were both of those, of course, but now they also were sales tools. By today’s standards they were primitive sales tools, and often garish, but there was a deliberate attempt to make covers analogous to display advertisements, the purpose of which was to generate sales.

Fast forward a few decades, to the era of digital books. By the time the first ebooks began to appear, paperback covers and hardback dust jackets had matured considerably. Competition had forced publishers to pay attention not just to marketing angles but to overall attractiveness of their covers. Still, many printed books had pedestrian covers.

After all, there were ways other than the covers themselves that the books came to the attention of the public, such as catalogues and display ads. In such venues more than the book cover was shown. Commonly there would be a few lines about the book’s contents and perhaps even a few celebrity endorsements, “celebrity” varying from niche to niche, of course. The cover didn’t carry all the marketing weight—or even most of it.

For the most part, ebooks weren’t listed in printed catalogues or given ad space in newspapers and magazines. They didn’t have auxiliary means of promotion. They had to promote themselves, which meant their covers took on a more crucial role for them than covers did for hardbacks and paperbacks.

In the “old days,” an author or publisher could get by with a ho-hum cover. If the cover didn’t indicate the niche of the book, well, that could be made up by the text in the catalogue or ad. Now there was no catalogue or ad. The cover had to do all the work, and it had to do it right, else the book wouldn’t sell.

A detective thriller that looked like the hardback cover of The Sun Also Rises wouldn’t get thrilling sales. A plain-text cover, such as The Pyramids of Egypt, might get by, if the text said what needed to be said, but was getting by enough, given the competition.

Over the last decade ebook covers have become increasingly sophisticated. They often surpass covers of hardbacks issued by the Big 5 publishers, some of whom produce beautiful, artsy covers that fail as marketing tools, with microscopic or skewed text or images that relate neither to the genre nor the book’s storyline.

Today’s indie author probably isn’t today’s indie cover designer. When ebooks first appeared, simple, home-grown covers often were enough, so long as they weren’t outright dreadful, but that phase didn’t last long. Competition saw to that. Few authors have the skills needed to produce top-rate or even just respectable covers, but many try their hands at it anyway. The results usually are less than adequate.

There seem to be two things at work here.

Many writers are on such tight budgets that they shrink from spending several hundred dollars on a professionally-made cover. Will their books sell enough to make up even for that cost?

Other writers don’t yet understand the purpose of ebook covers. “A cover’s a cover,” they think, as though only their books’ words are important. They don’t appreciate that if people don’t get past their books’ covers, they won’t get to their books’ words.

Most of these people likely are doomed to few sales. For some it will be well deserved, since their prose won’t deserve good sales anyway, but for others, who objectively are good writers, the disappointment will be keen. They will complain that, despite what some say, there isn’t any real market for ebooks or that the ebook tide has crested and print books are the wave of the future. Such people will disappear from ebook publishing.

That will leave those who have varying levels of savvy. They will know that their books’ covers are crucial to their books’ hoped-for success. The ones who experience wide sales will know to give not a small part of the credit to their cover designers. They will acknowledge that, in the minds of readers, “what you see is what you get.”